In order to find our way in a very complex world, we tend to put people, groups or things in categories – this is first of all an evolutionary and also normal process (Domsch, Ladwig & Weber, 2020). However, in order for these categorizations not to end in discrimination, an active learning and reflection process must take place and one’s own patterns of prejudice must be revealed. The aim of this article is to take a look at discrimination in the workplace with a focus on gender-based discrimination, to stimulate reflection and to provide ideas on how societies and individuals can deal with the issue of discrimination. For this purpose, we spoke with our Tiba freelancer Mona Nielen and will support her statements with current figures and data on the subject of discrimination.

Discrimination in the workplace

For many decades, topics such as racism, gender pay gap, #Metoo or homophobia have been part of the political and social discourse. A lot has happened in recent years and some are asking themselves the question: Do we still need to talk about discrimination in the workplace? The answer is clear: yes! Discrimination in the workplace continues to be an important issue because it is pervasive. According to the fourth joint report by the German Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency, around 30% of those surveyed have experienced discrimination in the workplace – as witnesses or as affected persons. The triggers for this are varied: discrimination in the workplace is particularly often based on gender, age, race or disability.

Mona, what are your experiences with discrimination in the workplace?

Mona: It is difficult for me to attribute discrimination to the mere “womanhood”. I have a set of criteria that could theoretically lead to discrimination – as a young woman (30 years old) wearing a headscarf.

First of all, categorizations are part of normality – we simplify the world by putting people or things in certain drawers. This also happens regularly in the professional context. For example, I remember various team rounds or trainings in which the “women’s perspective” in the room was explicitly asked, as if there was such a thing as a clear and unambiguous “women’s perspective”. In my opinion, this alone is not seriously discriminatory. But there are situations in which, for example, men tend to evaluate women in feedback discussions especially with regard to their emotions or describe them with terms such as “sweet” or “charming” – terms that have no place in the business context. I also often experience that employees bring in good ideas, but they are only heard when a male colleague addresses the same point. This is a frequently observable phenomenon.

Most of the time, however, we do not consciously perceive these situations, as they pass quickly and in a certain way we have also learned not to make a “big thing” out of it. In this context, the term “power woman” also comes to mind, which is often used to highlight the good performance of a woman. I’ve never heard of a power man.

Personally, I have encountered more direct forms of discrimination. For example, I’ve seen myself told, “I wouldn’t take you to the customer with your characteristics, – a young woman wearing a headscarf.” When a colleague once suggested me for a project, my portfolio was also requested, which of course included a photo of me. I was rejected on the grounds that you could not hire a woman who wears a headscarf as a trainer. My colleague then firmly supported me and the customer’s opinion ultimately changed as a result.

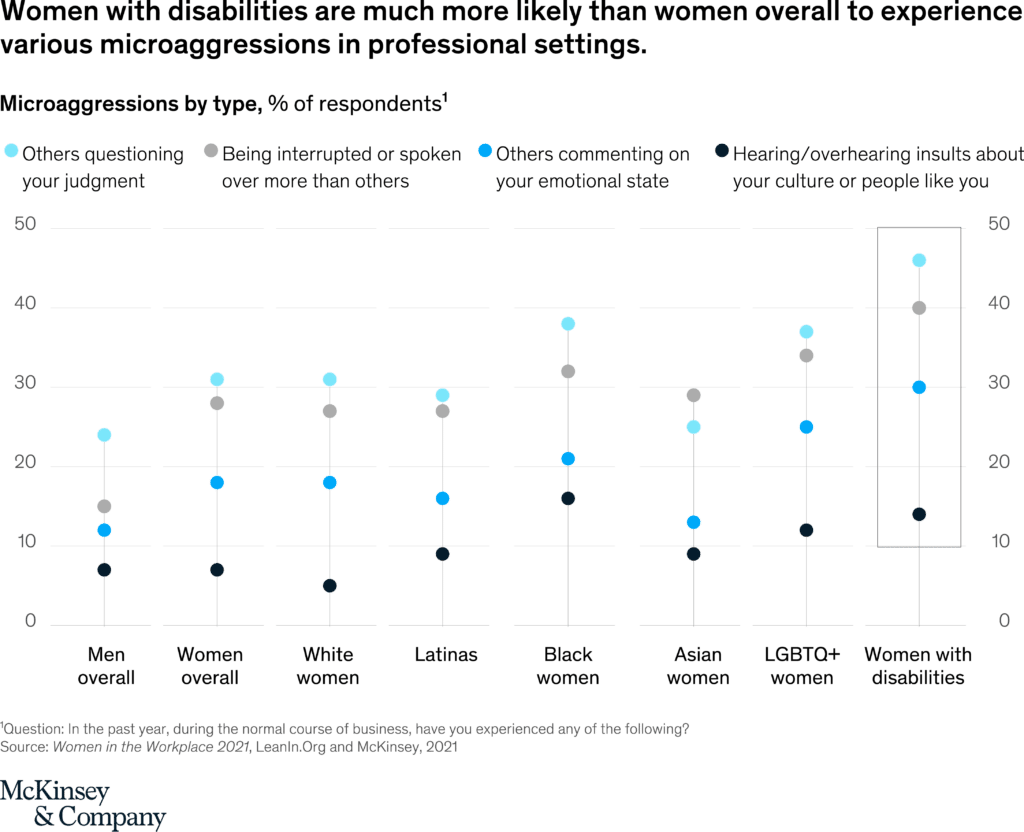

Mona’s stories also coincide with the current data situation. In fact, it is particularly the case that accumulation of (external) characteristics can lead to discrimination and also increases the number of discriminatory incidents. For example, a recent study by McKinsey shows that women of color or women with disabilities experience a significantly greater degree of microaggressions than white women (see figure below).

Microagression by type (McKinsey, 2021)

But there is also the opposite reaction, I am deliberately contacted because I am perceived as interesting. This can be positive, and sometimes this attention is something that leads to making valuable contact. But this positive engagement sometimes has an aftertaste, because I am more than a woman, or than this headscarf.

You have been working as a freelancer and trainer for 8 years. Have you developed a specific solution in dealing with discrimination that works for you?

Mona: Actually, I act in this context depending on the situation. My strategies depend on what I can afford (financially). If, for example, an agency and colleagues advise me not to put my photo at the top of a homepage, but rather the photo of a male, possibly older colleague in order to make a “better” first impression: sometimes I think pragmatically and economically in these situations and follow the advice. Sometimes I can or would like to afford a more relaxed attitude: The customers I want to work with and who fit me (in the long term) will not care whether their business coach, trainer and moderator wears a headscarf or not.

From your point of view, has anything changed noticeably when it comes to discrimination in the workplace since you started working?

Mona: Basically, I believe that the topic of gender discrimination is much more of a topic of discussion. For example, the topic of gender has already arrived in various “bubbles” in recent years. At least in the spoken word amongst each other, I notice differences. Whether something has really changed in the pay gap or in the proportion of women in management positions, current studies certainly provide information.

In fact, the figures prove that women are still severely underrepresented in top management: According to the DIW’s Manager Baromter, the proportion of women on the boards of the top 200 companies (measured by turnover, excluding: the financial sector) was just under 15 percent in autumn 2021. In 2020, however, this figure was still 11.5 percent.In 2021, according to the Federal Statistical Office, the pay gap between men and women was 18 percent of the average gross hourly earnings of men. In addition, women with comparable jobs and qualifications would earn an average of 6% less per hour than men (last survey: 2018). In 2010, this figure was 7%. Although gender equality has been laid down by law for decades, Germany still seems to have some catching up to do in this regard. The Gender Equality Index 2021, which is collected by the EU, further substantiates this assumption. With 68.6 out of 100 points, Germany ranks 10th among all EU countries.

You mentioned earlier a colleague who supported you with a customer. Can you tell us more about your experience with allies?

Mona: There is a difference between what I wish for socially and how I act very pragmatic. Socially, I would wish that I no longer need many of my strategic “moves”. I often need a person who is compassionate towards me and stands up for me. My biggest supporters are men, whether customers or colleagues. I also noticed the same phenomenon in the context of a research project at the university where we conducted interviews with women in management positions. It was often described that women compete with each other, among other things, because there are so few positions for women at management level in some industries. Personally, I have rather experienced that we women stick together and, for example, consciously respond to what the other women have said in the meeting in order to strengthen their voice. Allies can also help to create visibility by deliberately writing or staging a woman’s name under a joint project, or by specifically presenting the group result to colleagues, holding the customer pitch, etc.

The allies addressed by Mona Nielen are also becoming increasingly relevant in scientific studies. These supporters, often referred to as “allies”, are generally defined in the literature as people who do not belong to a particular discriminated group but support them with their behavior or statements. In the area of discrimination against women in the workplace, effective “allyship” can be defined as behavior that supports a woman’s career, reduces negative comments or creates a sense of support (Cheng, Ng, Traylor, King, 2019).

Allies are seen as an important help in reducing prejudice and creating more equal conditions for all, if only because the people discriminated against do not have to fight discrimination alone (Ashburn-Nardo, 2018). Especially in situations in which a discriminating person is directly confronted, allies could play an important role: In a study, for example, it was shown that comments by men that are directed against specific behavior that discriminate against women would generally be perceived as less negative than if this is expressed by women. Here there was less defensive behavior and a lower feeling of irritation. If you are part of a discriminated group (in this study: both white women and African Americans) and speak out against discriminatory behavior, you would be perceived as “complaining” (Czopp, Monteith, 2003). Incidentally, similar reactions were also found among uninvolved third parties who witnessed a confrontation with the discriminating person. Allies were perceived as much more convincing compared to the person concerned (Rasinski, Czopp 2010). The studies prove that it is essential that non-affected and non-discriminatory persons in particular bear a great responsibility in order to prevent discrimination in everyday (professional) life in the long term.

In addition to the positive ethical component of equality, there are more and more studies that indicate that companies with high gender diversity are more successful. Especially women in top management promise a significant increase in business success. How do you explain that?

Mona: Especially in projects that are absolutely dependent on good cooperation and well-functioning complex collaboration and problem-solving processes, good team dynamics and cooperative cooperation play a decisive role. Basically, through their socialization, women could bring the potential to bring an empathetic or collaborative leadership style into companies. But you can’t generalize that. The strength of diversity can lie in the fact that the skills and weaknesses of the employees balance each other out and that new innovations, more creativity or new solutions arise precisely through different perspectives, backgrounds of experience and opinions and the associated friction potentials, if well managed and moderated.

The more diverse, the more successful: Companies that have a high degree of diversity are more likely to be above average profitable. This is according to the McKinsey study “Delivering Through Diversity”. This is particularly evident in Germany in the proportion of women in top management (Executive Board plus one to three levels below): With a large proportion of female managers, the probability of above-average business success doubles.

What role could leaders play in support?

Mona: In general, managers have very strong influence, which is clear: the more important the topic of gender is to a manager, for example, the sooner the topic will be accepted and implemented in the organization in the long term – we know this from change management. Executives act as sponsors and play a significant role in ensuring that changes are actually accepted. Without the active commitment of the executives, it will not work. However, it is also not enough that certain rules are imposed “from above”, it must be incorporated into the organization and an active examination of the topic takes place. All employees must understand why the topic is so relevant for the company. This is exactly where, in my opinion, the executives come into play: communication, communication and communication are the key here.

Current topics of the world of work are regularly examined in the “So-arbeiten-Deutschland-Studie”. This is also the case with regard to gender discrimination in the workplace: 91 percent of those surveyed stated that men and women should be treated equally in the workplace. However, seven out of ten respondents demanded that impulses for equal treatment should come from management. Employees see objective performance evaluations (65 percent), a corresponding corporate culture that promotes equal opportunities (56 percent), and the flexible design of everyday working life (41 percent) as the most effective means of achieving equality.

In your opinion, which instruments are suitable for the advancement of women?

Mona: Basically, I think that in order to really change a culture, a structure for it must always be created. Culture and structure are strongly dependent on each other, new structures create new manners. This is also a management task: for example, when it comes to introducing gender guidelines and appointing gender officers. It is important that this new role has connectivity in the organization and that the role is not a superimposed construct. It must be made as concrete as possible and, for example, a talking item must be on every agenda.

This can be unpleasant at first and not work well because it is unfamiliar, uncomfortable and time-consuming. The following applies here: “Just do it”, in the sense of being as simple as possible and, above all, getting into action. The goal is to generate more visibility for women and their perspectives, experience and expertise. Only when these spaces are actively created, instead of just talking about the fact that it is important, do opportunities for development arise, changes and thus improvements happen. That is why I am a proponent of the women’s quota. Not as a rigid system of course, you should always work with regular feedback loops in change processes and reflect on the new structures and behaviors in order to be flexible enough to react to needs, criticism and suggestions. This is exactly why practical tests are needed: What works? Which adjustment screw still needs to be turned? There is certainly no one-size-fits-all solution in this area. You have to communicate with all those affected by the topic in the organization and go into constructive exchange. Once the change has manifested itself, there may no longer be a need for a fixed quota.

At this point, many thanks to Mona Nielen for your insights and openness.

Literature recommendation by Mona Nielen, for all those who want to deal with the topic of gender justice in a humorous and provocative way: “How to become successful without hurting the feelings of men”, by Sarah Cooper