A guest article by Conny Dethloff

In my view, the hype around agility in companies has recently taken on increasingly bizarre traits. It is like admiring the cutlery before every single meal and debating how beautifully shiny it is before we start eating. With this article, I will attempt to demystify agility and the methods that go with it.

A little thought experiment

Let’s imagine aliens visiting us on earth and seeing humans riding a bike for the first time. They don’t know bikes and certainly not how to ride them. They think: “Wow, this thing has only 2 wheels and the humans do not fall over. Amazing.” They’re watching us to see how we manage this trick. One of the aliens observes how humans ride the bike and thinks to himself: “That’s it. Mystery solved.”. On the basis of these findings, he invents a method of how to ride a bike from now on and teaches his colleagues.

Meanwhile, they have given a name to this methodology and regularly celebrate it. They ask us humans about this methodology in the context of riding a bike and we are surprised because we don’t know this method, we have never heard of it. The aliens wonder how we still manage to ride a bike.

Do you recognize the parallels to agility? What would happen now if we exchanged the term “cycling” for “being agile”? I think it is very similar. You look into companies that are successful. You observe all kinds of things, what they do, which processes and methodologies they use. However, if you try to describe what you observed it becomes difficult because you don’t really grasp the actual core of why these companies are successful. It is not the processes and methods that make a company successful, but the people in the companies who use these processes and methods.

The reasons for success in complex environments cannot be described, they can at best be observed. It is then difficult to adapt those reasons for yourself as this would require a description of what was observed. I have once reflected this fact on the topic of leadership and formulated a theory that only bad leadership can be described as it does not accept this incompatibility.

Agility has primarily nothing to do with methodology

Precisely. Agility is first and foremost about the mindset of people who think and act. It wants to build on that. Again and again, I heard questions such as:

- How often do we need to perform a stand-up in the team, does it really have to be every day?

- How long should this last?

- Can we have a sprint duration of three weeks?

I always describe this kind of questions as lacking context as they do not have anything in common with the actual meaning of agility. Returning to the comparison with riding a bike – it is as if my son, when learning how to ride a bike, had asked me how many minutes until he had to lift out of the saddle and how many turns of the pedal until he can sit down again.

The core questions behind agility are these:

- Who is our “customer”?

- What needs and wishes does our “customer” have and how can we quickly identify changes of these?

- Which services and products can we use to quickly fulfil these needs and wishes, and why can no one else do it better than we do?

- How can we, as a team, constantly improve in terms of the questions above?

Whenever you ever hear the question “Do we have to be agile?”, you should remember that the questioner actually wanted to ask “What does agile mean?”. Once you have understood agility you know that asking “whether” is just as irrelevant as the question “do we regularly have to eat?” or “is it important to breathe?”.

Agility is not static and can only be introduced through agile ways of thinking and acting. In other words, agility can only be introduced in an agile manner. A contradiction? Of course. The whole point is liveliness. The way is the goal here. Agility must never be the goal, only a means to an end.

A method is neither agile nor non-agile. Any assessment of adjectives without context, in this case the assessment of a method, will always be devoid of meaning. Without context, there is no difference between agile and non-agile. Let’s use another simple example, this time from the world of sports. A gymnast is flexible. Does it therefore make sense to label each footballer, just because they are not as supple as a gymnast, as not flexible? No, of course not. The important issue is how much mobility is actually required in order to be successful in the respective sport. And that is the context I bring into play here.

Complexity cannot be handled through methodology

It is about choosing a suitable method. A hammer is not useless as a tool just because I cannot use it to put a screw into a wall. And plainly, it is the human being who is responsible for choosing this method. Just because you notice that in a project or across the board in a company you are not agile enough, you should never blame the method, such as “waterfall”, for this. Because even with this method you can be agile.

Selecting the appropriate method is only possible with the right mindset. Agility has nothing to do with the method used, but rather with the mindset of the people who solve a problem.

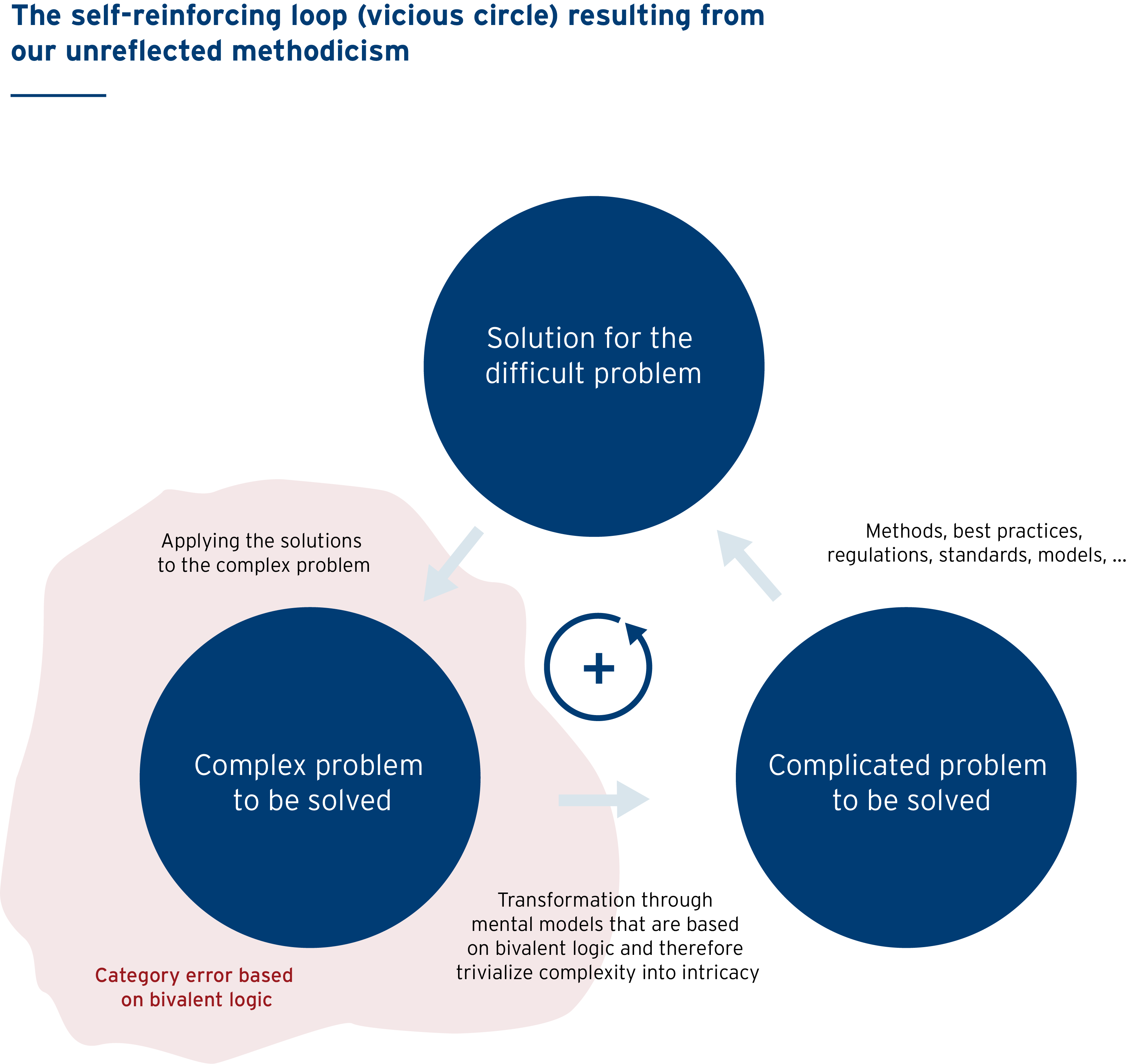

Unfortunately, the methodicism I perceive, to which we have succumbed, plays a trick on us. It prevents us from discovering the true meaning behind agility. I will now go into this by taking a closer look at the vicious circle of methodicism shown in the following figure.

Complex problems are not formally and logically describable, because complexity implies contradictions, but this contradiction is excluded within the framework of our logic. After all, methods are based on logic. If methods were contradictory, we would refuse to accept them as we do not see their added value.

So, in order to use methods as solution, we have to transform complex problems into complicated ones. This transformation has become so normal to us that we do not even think about it anymore. The solution found, which is based on the transformed complicated problem, is then applied to the complex problem.

In doing so, we make a category error. By making this mistake we are caught in a vicious circle. Vicious circle, because we are dealing with a self-reinforcing loop. We notice that very often the solutions found do not solve the problems. Of course, they don’t, they have nothing to do with each other because of the transformation that has taken place. However, this fuels the very uncertainty within us, which we actually wanted to overcome by using methods to solve problems. So, our desire for even more methodology and even more standards is growing. In the process, our problems are not being solved, but rather exacerbated.

I would like to emphasise again that I am not opposed to methods. Not at all. We just need to have confidence again when solving problems, i.e. feel and think more. Far too often, we look for a solution on the “outside” rather than on the “inside”. This way, humans become the tool of the method. Methods prevent taking responsibility for failure and thus stand in the way of learning. Methods should be means, never the purpose.

Cycling, to return to our initial example, is learned by cycling. This is an important rule that we normally follow without thinking about in private life but not in a professional context. Methodicism is in our way here. To learn SOMETHING by doing exactly this SOMETHING seems contradictory to us, as we cannot depict it logically because of its loop reference, and it is therefore not possible to describe in terms of methods.

So, agility can only be introduced through being agile. Japanese philosophy, on which the ideas and thoughts behind agile are largely based, offers some clues but this is often in the blind spot of our thinking and acting. Their martial arts have three stages of learning (Shu-Ha-Ri), which a student passes through from the beginning to mastering his/her art.

- “Shu” which is the first stage of learning, means roughly “receive or obey”. You learn by rigidly following the set rules. I like to describe this as the context-less following of processes.

- “Ha”, the second stage, can be translated as “to set out, become free, wander”. Here, the point is to interpret the context-less rules and standards and to vary them according to context. This also includes understanding the meaning and purpose of the methods to be used in order to to go beyond simply following them.

- Finally, “Ri” as the third and highest stage means “leave, separate, cut off”. This means leaving the set patterns behind to go one’s own way, guided by one’s own impulses. The experience and mastery of the rules is the prerequisite here to make a person independent of methods in the respective context.

At the level of the third stage, you have built such profound knowledge of methods that you purposely no longer use them to achieve success. We humans of the western society often remain on the first level “Shu”, because the transition from the first level to the second is hindered by the transformation from “complex” to “complicated” (figure above) when solving problems.

Author profile

Conny Dethloff was born in February 1974. In 1999 he completed his mathematics degree. He then directly went into economy, as a management consultant until late 2011, with a focus on corporate management and planning in various industries. Conny Dethloff is currently employed as manager in the field of Business Intelligence at OTTO GmbH & Co. KG where he is instrumental in driving OTTO’s digital journey in connection with data and BI. He describes his findings in this context in several blogs.